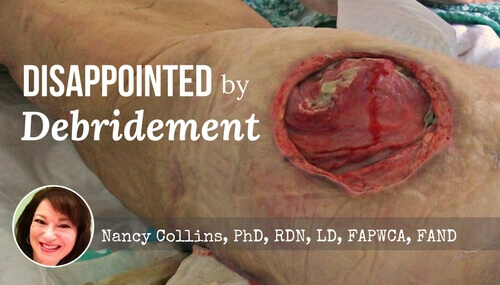

Plaintiffs often express shock and disbelief after eschar is removed, which often leaves a wound larger than the original size of the eschar.

Wound photo: “Stage 4 decubitus displaying the Gluteus medius muscle attached to the crest of the ilium” by Bobjgalindo is licensed under CC BY 2.0

“We were in shock and couldn’t believe our eyes. It was like half her foot was gone.”

“My husband and I were horrified when we saw what they did.”

“My sister and I looked at each other, and I just kept asking why?”

“I had to leave the room and go the bathroom to cry when I saw what they did to my mother.”

You might think these quotes are from people who have witnessed a shocking crime or some sort of violence, but they are not. These are quotes from family members, now plaintiffs, who are suing for poor medical care related to a chronic wound. Their shock all had one thing in common—it came after seeing a wound that was surgically debrided.

As wound care practitioners, we know that in order for a wound to heal, it is necessary to remove the devitalized tissue, or eschar. This is done with a scalpel and forceps, and often the wound does appear much larger once all the eschar is gone.

The Patient’s Perspective

In reading the deposition testimony given by these plaintiffs, it is clear they believed eschar was the equivalent of a scab. As individuals who have skinned their knee know, the epidermis is sheared off, and after pressure is applied to stop the bleeding, the area will soon form a scab. After several days, the scab will fall off leaving a healed wound in its place. It is this process that the average layperson believes happens with all wounds. Unfortunately, this is not the process for pressure injuries where the damage begins deep within the tissue and the break in the skin is the so-called “tip of the iceberg.”

Eschar is not a scab. The tissue is dead, and it is necessary to remove it. Once that is done, the underlying tissue may have damage extending far greater than the physical size of the eschar. It is evident from their depositions that these plaintiffs did not understand the process of debridement and felt that harm was inflicted. If you put yourself in their shoes, it is pretty easy to see why. A nice intact piece of eschar looks neat and tidy. A wound debrided to red, bloody tissue can look scary.

Debridement Education

Before surgical debridement, a consent form is signed, so there is clearly an opportunity to review the process, the expectations, the risks, and the results. It is not hard to imagine that this process is rushed at times because of circumstances, but I encourage you to slow it down.

Typical consent form verbiage is:

The procedures necessary to treat my condition were explained to my satisfaction by the physician, and I understand that excisional debridement is the removal of all nonviable tissue.

It may help to review your consent forms and use simpler language, such as “cutting away unhealthy areas in and around the wound.”

It is imperative that the patient, if mentally competent, and family members understand the reasons why it is necessary to remove eschar and that the wound will look different after this process is completed.

It is not uncommon for plaintiffs to turn to Dr. Google afterward, and they often uncover information about enzymatic and autolytic debridement. They wonder why these methods were not offered as viable alternatives to the surgery. They feel that information was kept from them. The time to wonder this is surely not during a deposition. Make sure to explain all the available methods, and if surgical debridement is preferred, explain why it is the preferred option. As in most matters of medical care, open and honest communication goes a long way.

Mastering Patient Communication

While debridement is the example today, there are countless other examples of miscommunications that lead to discontent and lawsuits. The best way to avoid problems is to practice the acronym RESPECT. Randa Zalman, chief strategy officer and partner at marketing-communications firm Redstone, devised an easy way to help remember the salient points of communication skills.1

R = Rapport. Give patients your full undivided attention.

E = Explain. Ask patients a variety of questions so you know what is important to them.

S = Show. Show support for your patients.

P = Practice. Practice good communication as much as possible. Ask patients for feedback, identify communication roadblocks, and review communication techniques.

E = Empathy. Avoid being judgmental by providing encouragement to your patients.

C = Collaboration. Partner with your patients.

T = Technology. Technology makes it easier to communicate, but use technology carefully and don’t overdo it. A frequent modern complaint is that providers are typing away in the electronic heath record rather than listening and making eye contact.

Communication is the key to human connection. I would love to hear your stories of how you connect with your patients and what techniques you use. Please contact me at [email protected].

- American Medical Association. Six simple ways to master patient communications. AMA Wire website. https://wire.ama-assn.org/education/6-simple-ways-master-patient-communication. Published June 22, 2015. Accessed February 21, 2017.

What do you think?